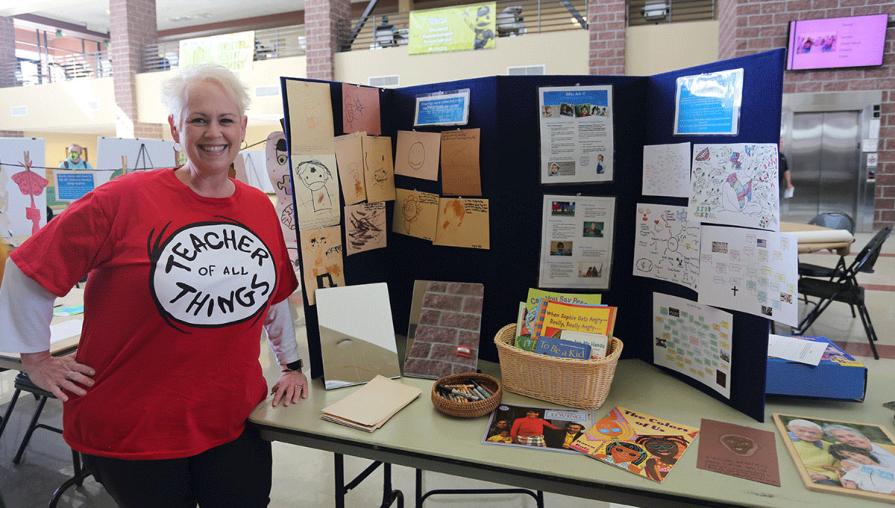

In the “Who am I?” Art Exhibition on display at the TMCC Diversity Fair, children from the E.L. Cord Child Care Center responded to the prompt by drawing their self-portraits. Next, the participating children were interviewed by Early Childhood Education students, under the direction of TMCC Early Childhood Education faculty Jencie Davies, explaining what they had drawn. The line drawings share few similar characteristics: mostly, the subject is pictured in the center stage where facial features include eyes and a single upturned smile. Identity, for young children, centers around the people, things and situations they like and many of their narratives begin with the phrase “I like...”

Davies explained that these fundamental expressions of self become more complicated as we age. As children develop they become more aware of the different components of their own selves. Selfhood extends to family roles, social roles, to our stage in life, as well as to the different facets of identity that include gender, gender identity, race, social class, and ethnicity, to name a few. Eventually, we begin to occupy more than one role in a single domain: daughters also become mothers or even grandmothers; from the singularity of our initial moments of existence, people form complex webs that map the countless permutations of who we are.

TMCC’s Diversity Fair, held on March 1 on the Dandini Campus, was a multi-disciplinary inquiry into the nature of diversity, and how identity, history and other societal discourses can define the parameters of how we understand ourselves as well as the identities to which we belong.

Students, faculty, staff and guests from a diverse range of disciplines contributed to the discussion from biological, anthropological, chronological and personal experience for a day that explored the multi-faceted ways in which we can identify ourselves, while opening new understanding to our biases against race, ethnicity, age and ability, to name a few.

In addition to student-led poster presentations, the Diversity Fair included a wide variety of activities, including a Welcome and Land Acknowledgement, a presentation on Ageism and Aging, FREE Book Club discussion on “Mapping Indigenous History” and a live webinar focused on “Teaching Traditional Ecological Knowledge” as a part of the Native Ways of Knowing series.

“Students who participated in the Diversity Fair examined poverty, ageism, social class, and race,” explained event organizer Anthropology Professor Dr. Joylin Namie. “The event invited students to step out of their roles as passive observers and to interact with each other and with diverse ideas through critical thinking, speaking, drawing and mapping their thoughts and actions. This kind of interdisciplinary, critical thinking can lead new insights into their own thought processes and ideas.”

The Science of Skin, Anthropometry and Ageism

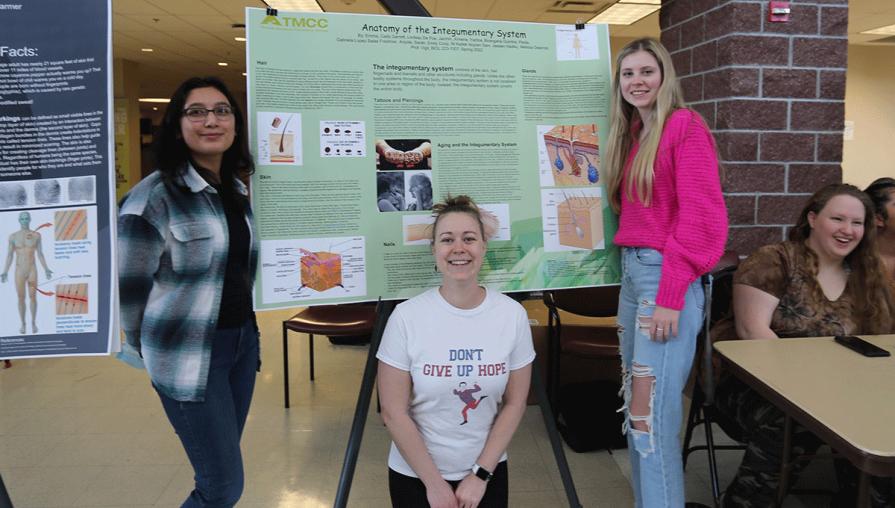

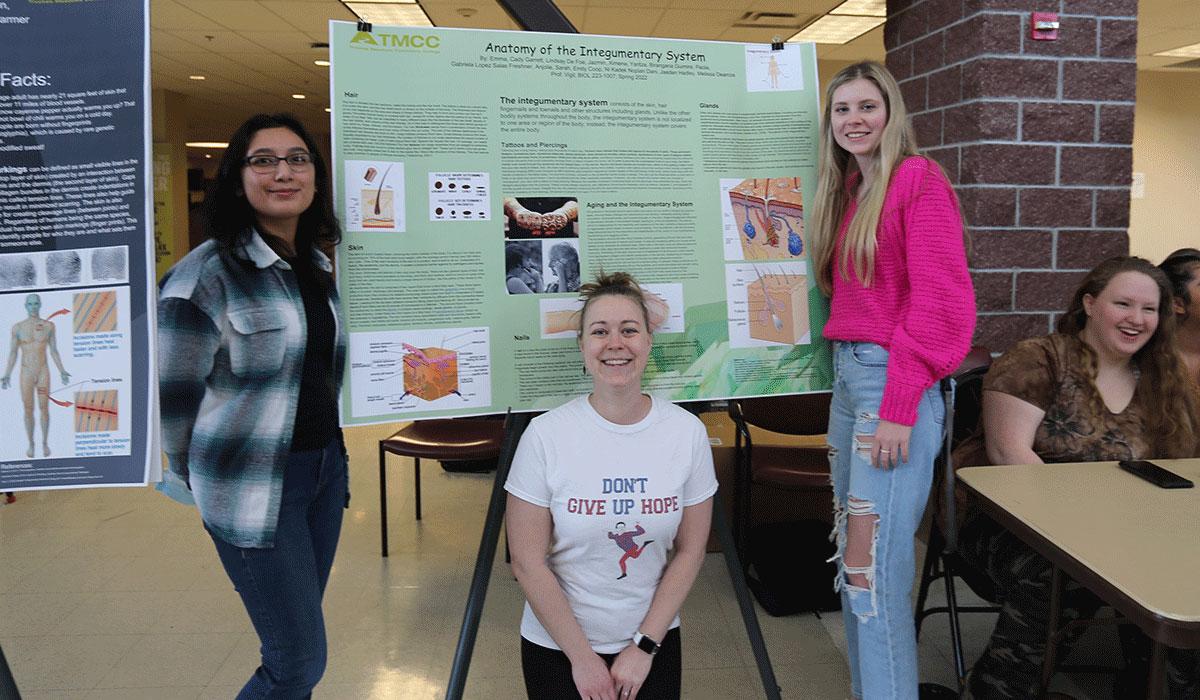

While our definitions of ourselves often originate from internal parameters, such as personality, psychological disposition or even our wants and dreams, exterior and surface-level markers can also play a huge part in how we conceive of ourselves, and where we may or may not find belonging. Students in Biology Professor Dr. Cecilia Vigil’s Anatomy and Physiology class presented their research on the “Anatomy of the Integumentary System.”

“It’s otherwise known as skin,” said student Sarah Freshner. “But it also includes hair, fingernails, all the glands, the dermis, the epidermis—and the different layers of them and how each one of them affects our skin and how we interact with the world.” As the body’s largest organ, skin has both a protective and sensory function: keeping out unwanted germs or viruses, while regulating body temperature and providing sensory feedback via touch.

Paola Tavares Nava, another student involved in the research for this project explained that skin pigmentation comes from the amount of melanin produced by melanocytes in the stratum basale layer of the skin. “We all have different pigments, and that’s the reason why we all have different skin colors. But if you think about it in terms of diversity, it’s clear that we are all different, but under the lens of science, and in particular anatomy, the way that our bodies work is the same.”

The group also examined the impact of external applications to skin, such as tattoos and piercings, as well as aging. “I think this research really added to how I think about culture,” Tavares Nava said. “This is especially true about the Black Lives Matter movement. It’s important to consider how our skin is formed.”

Skin also played an interesting role for research conducted by students in Anthropology 102, or the Introduction to Physical Anthropology class. Students examined various facets of anthropometry, or the various methods by which we can measure and identify an individual. Through a historical survey of craniology, fingerprinting and facial recognition software, students sampled a broad spectrum of past, present and future methods of criminal identification.

Sidney Barnhart, an animation/graphic and media technologies major, explained that misidentification tends to happen using these kinds of anthropometric measurements. These misidentifications are a result of interpreter bias, but also—especially in regards to facial recognition software—how the technology was developed and tested. Barnhart cites a 2020 documentary film Coded Bias which tells the story of how MIT Media Lab researcher Joy Byolamwini discovered facial recognition software fails to see dark-skinned faces accurately.

“I was on the current uses team... so we looked at fingerprinting as forms of misidentification using these measurements and how they can be misused... a lot. And so I think a lot of it was looking at case studies and seeing specific cases that misidentified people and ruined their lives based on the biased interpretation of data,” she said. “Misidentifying people and being used in poor income communities affects people of color more than others, which is crazy considering it doesn’t even pick up their faces.”

And while it is interesting to consider both skin and our faces—arguably the visual attributes we align with our own conceptions of who we are—Dr. Theresa Skaar from the UNR Sanford Center for Aging’s presentation on “Aging and Ageism” demonstrated that these are not timeless qualities we carry, either. Instead, aging carries its own biases as it moves us forward. After all, in the near future historically a large number of people will be over the age of sixty, changing the distribution of old versus young.

Ageism—which is bias or discrimination on the basis of age—arguably impacts both young and old. The perception that teenagers are dangerous or that those who are older are slower or incompetent are two of many attributes of ageism. Skaar’s presentation illuminated how ageism stems from our relationship to our own aging. In 2020, people spent over $16.7 billion on plastic surgery with 42.9% of those procedures specifically on anti-aging and body contouring services.

Understanding ourselves and coming to terms with our own ever-aging existence is the first step, she said, in countering the biases we hold toward ourselves and others. And once we are aware, then we can work toward integration and activism for both ourselves and others.

Ableism and Adaptive Sports: Wheelchair Basketball

Have you ever played basketball? The sport, which was invented in the 19th century, was intended to foster teamwork. Since, basketball has grown (literally) be known for the lanky athletes that charge up and down the court, dribbling and shooting to earn the coveted three-point shot. As a part of the Diversity Fair events, Scott Youngs and Patty Rollison, members of the Silver State Highrollers, hosted a workshop in wheelchair basketball for TMCC students.

Replacing your legs with wheels changes the game, to say the least. Yet, both Youngs and Rollison have been competing in adaptive sports for most of their lives, demonstrating that what it means to be “able-bodied” is just what it sounds like: it’s no small feat to dribble a ball in a wheelchair capable of turning a dime. That takes a lot of practice, skill and... guts. And yet, when it comes to the question of “able-bodied”, that, too, can be complicated.

Yet, more than 23 percent of the citizens of Nevada are living with disabilities, more than a full percent greater than the average rate in the United States. One in five adults—more than 53 million people—in the country has a disability of one form or another, with state-level estimates ranging from 1 in 6 in Minnesota to nearly 1 in 3 in Alabama.

And yet for athletes like Youngs and Rollison, that definition hasn’t prevented either one of them from playing ball. Youngs has been playing wheelchair basketball for over 30 years. Rollison, too, has a long, decorated athletic legacy despite a long-term spinal cord injury. She started playing Open Adaptive Tennis in 1984, and by 1996 was ranked as the top women’s wheelchair tennis player in the country, as well as fifth worldwide. Like Youngs, she has also been playing wheelchair basketball for over 30 years.

She said being around others who played sports in wheelchairs inspired her to get involved. “I learned a lot—how to transfer, how to handle myself, and to travel. But, mainly I learned how to live,” she said.

In addition to playing wheelchair basketball, Rollison goes to rehab hospitals to speak to those who have been injured. “I go to the rehab hospitals with newly injured people and say ‘you can do this.’ You can do whatever you want.'”

As members of the Silver State Highrollers, both Youngs and Rollison hold a consistent weekly practice schedule and play a complete league season from August to April. At the Diversity Fair, they taught TMCC students nuances of the game: that you can only push your chair twice before having to dribble to avoid a traveling call, or how to use the rotation of the chair’s wheel to help retrieve a ball that’s gone courtside.

For students who re-learned a game they might have been familiar with on two legs, one thing became very clear: identity is a fluid thing, and one that grows along with us as each of us becomes more complicated in an increasingly diverse world. And yet, despite all of that, we shouldn’t be afraid to take part. All of us, in one way or another, can belong.

For Rollison, this is the message she delivers to people both in hospitals and in settings like the TMCC Diversity Fair. “It doesn’t matter how old you are or any kind of physical impairment. You can get out there, and do it,” she said.

For more information about TMCC’s Diversity Fair, contact TMCC’s Equity, Inclusion and Sustainability Office at 775-673-7072.