It’s a beautiful Sunday in October, and TMCC Education Professor Micaela Rubalcava—wearing a mask, sunglasses, a jean jacket, and jeans with knee pads—is putting the final touches on her additions to the “Brave New World” chalk mural that is this year’s F.R.E.E. event, one in a series from this interdisciplinary learning community operating at TMCC since 2003. The collaborative mural, a 50-foot diameter circle in the shape of planet earth, is the result of Rubalcava’s interest in “Global Praxis,” a topic she’s developed over ten years of research and practice, forming the foundation of her forthcoming book, Teach to Transform. Simply put, Global Praxis facilitates diverse student success by connecting classrooms to big-picture, real world outcomes.

“That’s exactly what this outdoor education project is,” Rubalcava said as she filled in chalk squares of the mural with renditions of honeybees, frogs, and rabbits. “It’s where we take the education standards we need to learn to be a good educator and we open it up to healing the world… [today] students are disconnected from what they are learning in math, science, technology, engineering—whatever it is—social studies, humanities... [these subjects are] disconnected from real-world problem-solving.” By asking students to visually depict the “Brave New World” that awaits after COVID-19, Rubalcava is pairing academics with cultural perspectives into the imagination of environmental art, which is exactly the point of Global Praxis.

“When we don’t link education to the real world, we get ourselves into a circumstance where we’re completely dehumanized, under pandemics, don’t have enough resources, we can’t even teach students in the way we want to teach them,” she said. Although this year’s F.R.E.E. event looks very different from previous years due to the need to be socially distanced, it nonetheless shares traits with previous iterations: weaving core subjects into culturally-sustaining STEAM education (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Mathematics), scaffolding national curriculum standards into school-community engagement, and prioritizing environmental justice studies.

“Just being able to have this opportunity and experience [is so important,]” she said. “Students are paranoid right now, they don’t know what to do, they feel worried and nervous and they don’t know how to interact. And just to give them a space to interact safely and to feel connected to campus, is what F.R.E.E. does generally, but also specifically during this COVID time.”

Becoming an Educator

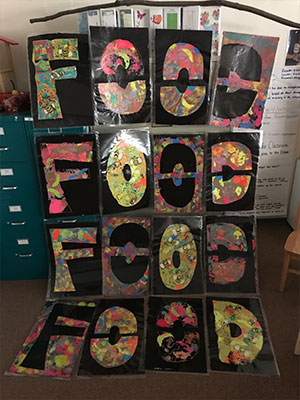

The FREE event in 2019 focused on food, and brought a mutli-disciplinary examination all across the college.

Rubalcava wasn’t always focused on a career as an educator, although education is where she found a safe place to learn and grow. In 1965, she was a part of the first Head Start Class in Oakland, where she discovered a love of learning.

“It was a safe place for me. And from there, I just kept going to school...I graduated with honors from UC Berkeley, and I wanted to become a diplomat with my degree in development studies, to help advise developing countries. But I had a few professors at Berkeley, like Ronald Takaki and Pedro Noguera, who inspired me, and so I just slipped into education,” she said. From there, Rubalcava completed a combined Master’s and teacher credential program at Stanford, which led to her first classroom experiences at an elite all-boys school, Woodside Priory, and shortly thereafter in Salinas, CA teaching Latinx ELL students.

“[Those early teaching experiences are] what taught me to integrate the arts into the classroom to support visual literacy, along with bilingual education to nurture cultural and linguistic competence. I discovered that students loved hands-on activities; they loved visual learning; they loved diving in with languages and imagination, kinesthetic arts and… just jumping into cross-cultural creativity,” she said. “My first classroom experiences offered race-class-gender contrasts—European American versus Latinx, elite versus working class, all boys versus gender balance—and those differences motivated me to teach through diversity to engage cultures, multiple learning styles, and unexpected academic textures.”

Her experiences throughout her education, beginning with the Head Start program in Oakland to completing her Ph.D. at UC Berkeley, introduced Rubalcava to multi-racialism and anti-bias diversity—two ideas that she carries into her work as an educator at TMCC. “My teachers in that Head Start program were Black and White, and my classmates were completely desegregated at school... we learned together as students from every racial and ethnic group you can think of. And from that beginning, I perceived school to be a resource-rich space of multicultural desegregation, just like academic learning is supposed to be. The role of public education is to grow democratic participation and economic inclusion, just like how earth ecosystems are made resilient through diversity.”

Rubalcava leads a workshop for faculty and administrators on anti-bias education to reduce the biases we pick up in early childhood and carry with us, often implicitly. This can prejudice how we administer public resources in higher education, particularly in the classroom, where approximately 80 percent of instructors are white. Her workshop teaches Culture Conscious Listening and addresses the questions: how do you unlearn bias? And, more importantly, how do you become anti-biased? It’s not an easy process, but one she says is worth it.

Rubalcava brings these considerations to F.R.E.E., where a diverse learning community can reflect the myriad perspectives of various ethnicities, cultures, genders and socioeconomic statuses. “I was very conscious of making sure the student lead muralists for the “Brave New World” chalk mural offered different cultures and perspectives to the project. I sought out diversity, and now..., I mean look at this,” she gestured to the mural which depicts a multicultural community holding the earth at its center, surrounded by images of medical professionals in masks, a group of individuals beneath which the words “Brave Deaf Community” are inscribed by one of the lead muralists, who is deaf herself.

“I use my courses and endeavors on campus to cogenerate anti-bias culture consciousness for a more inclusive administration of our resources in a way that builds resilience and heals, to connect socially, emotionally, and economically. At least that’s my goal,” she said.

Educating Educators

Students in Rubalcava’s education classes do plenty of hands-on projects to engage every aspect of their learning. [Note: image taken prior to COVID-19.

Rubalcava describes her goal to be an “out-of-the-box” educator who is student-centered. Although she writes precise assignment rubrics and holds high expectations in her education classes, Rubalcava insists that her students co-lead class interaction by doing research and sharing discovery and research, writing at least twenty pages of academic prose over the semester.

“I want them to own their education,” she said, explaining that involving students in their own educational journey in this way makes knowledge “stick” more than spoon-feeding it to them through pre-packaged, standardized lectures and lessons. She also relies on a practice she calls “Diversity Circles,” which groups 3-5 students into race-ethnicity-gender-class diverse cohorts. These multicultural connections simultaneously provide each student with an academic support network.

This cogenerative education prepares her students for a career that, Rubalcava says, is a public service. “Education is one of the most critical institutions for systemic change,” she said. “If people want to be a part of the solution toward systemic inclusion and democracy, education is key because we are on the front lines of knowledge development, dissemination, and socialization. In fact, within the institution of education, the most important factor to student success is the quality of the teacher. So if you want to make a difference for the next generation, be a good teacher.”

In 2017 Rubalcava explored effective education when she participated in the Fulbright-Hayes Seminars Abroad Program with a cohort of 16 education scholars from across the United States to examine the privatized education system in Chile. Her forthcoming book, Teach to Transform, is a result of that experience and what Rubalcava studied during her Fulbright: comparing Chile’s privatized education system with Finland’s, where two opposite reforms had contrasting results. In Chile, the privatization reform lowered education quality, segregated students, and inflated costs. In Finland, robust public education resulted in high education quality, top student test scores, desegregated outcomes, and modest costs. Teach to Transform outlines Rubalcava’s ideas on Global Praxis, Multicultural Mindfulness, and learning communities for everyday educators. Transformative practices do not have to be fancy or even expensive, as Rubalcava has demonstrated over the years during annual F.R.E.E. events.

“Learning communities don’t require much, you can organize them from within the established schedule as it is. The F.R.E.E. model doesn’t rely on high tech solutions… the model takes the class schedule that is set up and brings together classes that meet at the same time. For example, all classes that meet at 9:30 a.m. on Tuesday could form an interdisciplinary learning community, and they would collaborate on projects that connect different course learning outcomes into a big picture theme. This year’s F.R.E.E. I had to rely on whoever was interested due to social distancing. But, the students and staff who are participating are bringing together multiple disciplines and perspectives to explore our theme about courageous global healing.”

The Power of Art

Rubalcava uses art to create meaning, both in the world at large and in the classroom.

Rubalcava brings art into the academic classroom to engage different intelligences with her diverse students. A visual artist herself, Rubalcava has shown her work in galleries in California as well as at TMCC. Her art comes from her early childhood where, in a single-parent household, Rubalcava was tasked with painting murals on the walls of the apartments into which she and her mom frequently moved. “We moved a lot,” she said. “We didn’t own a house, we moved from place to place. And every place we lived, my mother would give me some paint, and let me paint the walls. So, I’ve done it since I was little. In a way, I can’t help it.”

Her work, she said, is part of the complex of solutions needed to save the world. “All of my art is low-cost, big-expression, and about wholehearted environmental health and sustainability,” she said. Her materials are purposefully simple and accessible: chalk, tempera paint, reused poster boards, recycled butcher paper and brown paper bags, classroom crayons, pencils, and glue, and other recycled materials. “I try not to use anything that is specialized or toxic, nothing high-end, nothing you wouldn’t already have in your classroom. Everything about the way I approach art is about seamless accessibility.”

Accessibility is key to Rubalcava’s approach to both her art and her approach to education—making sure the message comes from discovery is just as important as the message itself. This is part of the reason she facilitates multiple intelligences in her classes, and practices unique approaches for holistic student learning.

“Our educational system focuses on linguistic and logical-mathematical intelligences, which means that students who perform well on standardized tests are the ones who are considered ‘smart.’ What this misses, though, is the [capacity] of the whole brain, which is infinite. There are at least nine different intelligences, and if you can activate them through holistic education, you support students in academic learning, so they do better at reading, writing, and arithmetic as they activate other cognitive aspects,” she said.

These other intelligences include visual (art), but also kinesthetic (physical movement), musical, intrapersonal (emotional intelligence), interpersonal (social), existential (big questions), and naturalistic. Visual and kinesthetic, according to Rubalcava, are critical. “They’re the baseline for all education, because if you think about it, that’s how babies learn: they grab something and put it in their mouth. That’s kinesthetic. They are observing and watching and they learn from doing what they see,” she said. Rubalcava uses art—especially outdoor art projects—to integrate visual, kinesthetic, and naturalistic intelligences. Physical education, too, can be used to develop holistic academics by integrating mathematics (sports statistics and geometry), science (nutrition and physiology), language arts (reading and writing about sports), teamwork and emotional regulation (learning to win and lose), outdoor education, and cultural movement, music, and visual arts within a comprehensive physical education program.

“In my classroom, you’re going to get all your intelligences respected and activated…. And you’re going to know how to do that for your own future students, moving forward,” she said, emphasizing that including visual, kinesthetic, and other learning modalities may be overlapped with logical, linguistic, and mathematical cognitive engagement. In other words, it’s about thinking outside the box and beyond what students are asked to do on standardized tests.

“One of my professors at Stanford, Larry Cuban, said that the biggest educational innovation in the history of American education was the day they unbolted the desks from floor rows to open the possibility of moving students around, shifting from top down teacher-directed education to collaborative student-centered education. So, I teach all of my students to take multiple intelligences theory to the next level, and that’s why I show them how to integrate a bigger picture of visual intelligence, one that uses visual arts to develop critical consciousness about equity and environmental sustainability, getting students to move inside and outside responsibly and to respect diversity and heal.”

A Pipeline of Future Educators

Every spring semester, Rubalcava teaches Education 208, an advanced class focused on special education. Unlike other education classes, though, her Education 208 classes are held at Marvin Picollo School where TMCC students get real, professional experience working with special needs children. “My students get direct immersion into the profession right out of the gate,” said Rubalcava. “It’s a unique and wonderful program.”

Co-Lead Muralist Vanessa Garcia (left) and Rubalcava (right) work on the “Brave New World” chalk mural for the F.R.E.E. event this year.

Students can expect this unique approach to their education at TMCC, said Rubalcava, who said TMCC is an institution that supports its faculty to innovate with new opportunities, approaches, and experiences. “TMCC is small, and we’re kind of like a family. We’re supportive of diverse learners, and we are willing to take chances to open doors and build skills.”

Although Rubalcava fell in love with community college long ago—and the students she finds on their campuses— she finds particular joy in her work in the TMCC classroom. “I really have all these wonderful students,” she said. “They are diverse, humble, and they use our coursework to move onward through intrinsic motivation. If you can tap into that with them, cogenerate education with our students, it’s one of the most beautiful experiences you can have as an educator.”

If this year’s “Brave New World” chalk mural is any indicator of the beauty that comes from this approach to education, the world has a chance at creating something beautiful, whole and hopeful.

For more information about studying Education at TMCC, contact the department at 775-673-7185.